Dogen's 'Being-Time' - Part 1

Introduction:

From my first ponderings as a young

child intrigued by the deep time of both

the fossil record and the cosmos alike, to the graduate level coursework in Einstein’s

theory of relativity that I managed to survive on my way to deciding against an

advanced degree in physics, I’ve always been interested in the nature of space

and time and the answers “out there” waiting to be found. Of course I now know

that space and time are not two separate entities at all; rather, they are so inextricably

linked as to only meaningfully be referred to as space-time. Ah, but I risk

getting ahead of myself.

|

| Dogen gazing at the moon |

I suspect that Dogen Zenji, the 13th

century monk so prominent in Japanese Zen, was likewise interested in what

answers might be found “out there.” What else could have motivated him to

embark upon a dangerous maritime journey to China

To study the Buddha Way

In my entire life there have been

only two books that intrigued me enough, were unavailable enough (or so it

seemed at the time), and were deemed important enough to “my search” that I was

prompted to photocopy the entirety of their contents from the only copies I

could find in order to study them at my leisure. The first of these was Hans

Reichenbach’s The Philosophy of Space and Time – copied at a nickel per page on a coin operated machine at my old

alma mater after my professor cited it in one of his lectures on the philosophy

of science. The other was the four-volume set of Kosen Nishiyama’s translation

of Dogen’s Shobogenzo: The Eye and

Treasury of the True Law – discovered as if a diamond in the coal mine of a

local seminary library. (No offense intended to any readers who might relish

getting lost amongst stacks of Christian theology texts!)

In my entire life there have been

only two books that intrigued me enough, were unavailable enough (or so it

seemed at the time), and were deemed important enough to “my search” that I was

prompted to photocopy the entirety of their contents from the only copies I

could find in order to study them at my leisure. The first of these was Hans

Reichenbach’s The Philosophy of Space and Time – copied at a nickel per page on a coin operated machine at my old

alma mater after my professor cited it in one of his lectures on the philosophy

of science. The other was the four-volume set of Kosen Nishiyama’s translation

of Dogen’s Shobogenzo: The Eye and

Treasury of the True Law – discovered as if a diamond in the coal mine of a

local seminary library. (No offense intended to any readers who might relish

getting lost amongst stacks of Christian theology texts!)

At this point it should come as no

surprise that Uji is one of my

favorite fascicles of Dogen’s Shobogenzo.

Variously translated as Being-time (Nishiyama,

1975), The Time-Being (Welch &

Tanahashi, 1985), and Existence-time

(Nishijima & Cross, 2009), amongst others, Uji is a treatise on the nature of time, our experience of it, and

the ramifications of our understanding (or lack thereof) of our true

relationship to it. Let’s see, then, if any of my scientifically oriented explorations

of the nature of space-time might be of assistance in making sense of a 13th

century Zen monk’s exposition of the nature of existence and time – being-time.

Here goes…

Dogen’s ‘Being-Time’

There are many ways to think about

time, one of which is to think of it as something that passes, or as something

that we pass through. This is the way that we commonly think of life and time –

dualistic, though it may be. Dogen’s realization, however, is that in addition

to this everyday way of thinking about time there is the reality that we are

time:

“Being-time” means that time is being; i.e.,

“time is existence, existence is time.” The shape of a Buddha statue is time.

Time is the radiant nature of each moment; it is the momentary, everyday time

in the present (Nishiyama, 1975, p. 68 – all subsequent translated passages

from Uji are also from this source).

The Universe Is Time.

So, what are we to make of this “we

are time” way of thinking about reality? Let’s veer into the scientific

realm in order to apprehend the big picture. Think of the Big Bang, if you

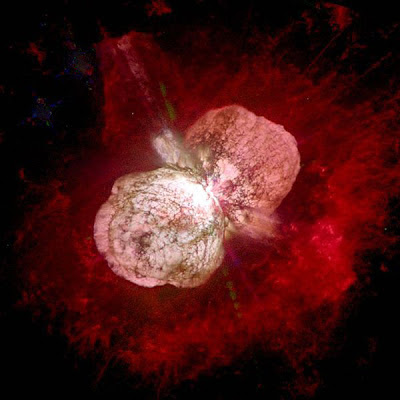

will. If you’re like me, when you think of the Big Bang you imagine something

similar to the image below. Actually, the image below is of a supernova, but

that’s also how I imagine the Big Bang to have happened – despite my

recognition that neither viewer nor vantage point could have then existed. Indeed,

how can a viewer, one who exists, precede all of existence; and how can a

vantage point, an existent point in space, precede the Big Bang’s creation of

any and all points in space?

If a void were to have existed into

which the universe then flowered into existence, then that void would have been

devoid of space and time (in addition to being devoid of everything else), for

space exists only in relation to things, and time only to their movement. Within

such a conceptualized void there would be no things, and thus no space to exist

between them. Within the void there is no time. For time to exist there needs

to be something happening, things moving – interstellar gas collecting into

nebulae and then condensing into stars; continents colliding and thrusting

mountains into the air; water raining downward, forming rivers and carving

canyons; a mind lost in concentration one moment, becoming bored the next. Neither

time nor space existed until the universe exploded into existence – until the

universe came into being. Thus, the existence of the universe and the time of

the universe are one. This is the being-time of the universe.

At this point an unconvinced reader

might be eager to suggest that we do away with the vantage point “outside of”

the Big Bang and focus only on the “inside”. Okay, let’s conceptualize a

vantage point “inside of” the unimaginably dense, undifferentiated unity that was

the pre-explosion seed of our universe, the seed which has since blossomed into

our universe. Keep in mind that there is no “outside” – that is why we’re

imagining ourselves “inside,” after all. The “inside” of this thingless,

spaceless unity that we are imagining would likewise be absent of time for the

same reasons that the void is absent of time. Thus, existence and time are one.

We Are Time.

Regular readers of this blog, in

addition to many other Buddhist practitioners, will be familiar with the teaching

of no-self. The teaching of no-self is essentially the recognition of the

emptiness (the lack of fixed and independent existence) of all phenomena,

including the collection of phenomena that we commonly refer to as ‘the self.’ Now,

the Heart Sutra’s insistence that ‘form is emptiness and emptiness is form’ might

prompt us to focus on emptiness as something that applies to the realm of

materiality (existence, being). Dogen’s Uji,

however, invites us to explore what emptiness means in the temporal realm as

well. Please keep this in mind as we continue unraveling what Dogen means when

he says “being-time.”

Okay, if the universe in its

entirety is being-time, then everything contained herein is being-time. Just as

the universe blossomed into being and with it, time, so we arise in form, each

with our own time. This is Dogen’s being-time. However, just as the Heart Sutra

encourages non-attachment to form (being), we should likewise refrain from

attachment to being-time. With that in mind let’s explore another couple of pertinent

passages:

Every thing, every being in this entire

world is time. No object obstructs or opposes any other object, nor can time

ever obstruct any other time (p. 68).

The central meaning of being-time is: every

being in the entire world is related to each other and can never be separated

from time (p. 69).

If We Are Time, Then Where Does The

Time Go?

We’ve gotten very good at measuring

‘the passage of time.’ With ‘the passage of time’ we came to refer to some

periods of time as ‘years’, and fragments of those years as ‘months’ and ‘seasons’.

With ‘the passage of time’ we went from measuring time as the transition of

daylight to darkness and back again, to measuring time in hours and minutes and

seconds. Note that all of these periods of time are based upon the relationship

between things – between the sun and the earth, between the moon and the earth,

and increasingly refined increments thereof. At the present time we have atomic clocks that define a ‘tick of the clock’ to be "the duration of 9,192,631,770 cycles of microwave light absorbed or

emitted by the hyperfine transition of caesium-133 atoms in their ground state

undisturbed by external fields" (General Conference on Weights and

Measures of 1967 as quoted in the preceding Wikipedia link). By the way, caesium-133 atoms are merely collections of

“things” that we are making use of in order to track ‘the passage of time.’

But if time passes, where does it

go? If time passes and we are time, where do we go? It is the seemingly

universally shared experience that time is something that passes us by that inhibits

us from enquiring more deeply into its nature. As Dogen says:

Even though we have not calculated the

length of day by ourselves, there is no doubt that a day contains twenty-four

hours. The changing of time is clear so there is no reason to doubt it; but

this does not mean that we know exactly what time is (p. 68).

Do not think of time as merely flying by; do

not study the fleeting aspect of time. If time is really flying away, there

would be a separation between time and ourselves. If you think that time is

just a passing phenomenon, you will never understand being-time (p. 69).

Why don’t we leave it right here

for now – even though we’ve only made it through two pages of what is actually

a much longer fascicle! Indeed, Dogen’s writing can be like a bramble, dense and

thorny; so let’s back away for a bit before trying to make further headway. After

all, we’re pushing the limits of our ability to comprehend – if only for the

time-being!

Please note: Though I’ve primarily

quoted from just one source translation, Nishiyama (1975), the reader might

want to check out others listed in the reference section below. At least a

couple of them are available online – links provided. I’ve made use of all of

them at one time or another as I’ve read and reread this piece. Be forewarned,

though, comparing any two translations line by line can yield some surprises. Furthermore,

due to the fact that Dogen was frequently writing from a place of understanding

that is difficult to put into any words at all, let alone words that are easily

understood, it behooves us to approach his writings from the vantage point of a

solid meditative practice. Until next time!

References

Cleary, T. (2001). Shobogenzo: Zen

essays by Dogen. In Classics of Zen Buddhism: The collected translations of

Thomas Cleary, Vol. Two. (T. Cleary, Trans.) Shambhala Publications by special

arrangement with University

of Hawaii Press

Nearman, H. (2007). Shobogenzo: the treasure

house of the eye of the true teaching (H. Nearman, Trans.) Published by Shasta

Abbey Press. (Dogen’s original work from 1240.) http://www.shastaabbey.org/pdf/shoboAll.pdf

Nishijima, G. W., Cross C. (2009). Shobogenzo:

the true Dharma-eye treasury, Vol. I. (G. W. Nishijima & C. Cross, Trans.)

Published by Numata

Center

Nishiyama, K. (1975). Shobogenzo: the

eye and treasury of the true law, Vol. I. (K. Nishiyama, Trans.) Published by

Nakayama Shobo Buddhist Book Store. (Dogen’s original work from 1240.)

Okumura, S. (2010). Realizing

genjokoan: The key to Dogen’s shobogenzo (S. Okumura, Trans.). Wisdom

Publications. (Dogen’s original work from 1233)

Welch, D., Tanahashi, K. (1985). The

time-being: Moon in a dewdrop – writings of Zen master Dogen. (D. Welch &

K. Tanahashi, Trans.; K. Tanahashi, Ed.) North Point Press. (Dogen’s original

work from 1240.)

Image Credits

Hubble telescope

image of a supernova (slightly retouched by author in order to remove extraneous "things") courtesy of Nasa via:

Image of Dogen

looking at the moon courtesy of Shii via:

Copyright 2013 by Maku Mark Frank

Comments

Post a Comment